Osu-Understanding the True Meaning and History of “Osu” (or “Oss”) in Karate

If you’ve spent any time in a karate dojo, particularly outside of Okinawa – chances are you’ve heard the word osu or oss. It’s shouted at the start of class, echoed in response to instructions, and used as a catch-all for everything from “yes” to “thank you.” To many, it embodies spirit, discipline, and respect.

But despite its popularity, osu is a word surrounded by misunderstanding. Its origins are often misrepresented, its meaning varies across cultures, and its use — especially in traditional karate circles — is far from universal.

This article isn’t intended to settle the debate about whether osu is right or wrong. Instead, I want to share my personal experience with the term — how I first encountered it, how my understanding evolved, and why I ultimately chose to stop using it in my own dojo. Along the way, we’ll explore some of the cultural history behind osu and why its meaning depends so much on context.

In karate, words matter. And sometimes, the smallest ones carry the greatest weight.

Key Takeaways

- “Osu” is not native to Okinawan karate — it likely originated from Japanese military culture and later entered certain karate styles, such as Kyokushin.

- The term is often interpreted as meaning “push and endure”, but it also carries associations with informal or subcultural language, including connections to yakuza slang.

- In many traditional budo settings, especially in Okinawa and Japan, osu is avoided in favor of more culturally appropriate expressions like hai or onegai shimasu.

- While many karateka use osu sincerely to express spirit and respect, context matters — what’s appropriate in one dojo may be seen as disrespectful in another.

- After a private conversation with Mabuni Kenzo Soke, I chose to stop using osu in my dojo, aligning instead with the language and spirit of Shito-Ryu tradition.

- This article is not about judgment, but about awareness — understanding where our words come from, and choosing them with intent and respect.

The History of Osu (or Oss) in Karate

Spend time in dojos across the world and you’ll quickly notice how often the word osu appears. For some, it’s a greeting. For others, it’s a sign of acknowledgment, spirit, or perseverance. In some dojos, osu is used so frequently it becomes the default response for everything — a verbal Swiss Army knife covering “yes,” “I understand,” “thank you,” or even “excuse me.”

This widespread use has given osu a kind of cultural momentum, particularly in styles like Kyokushin and Shotokan, as well as in offshoots and sports karate schools influenced by military-style training methods. In these environments, the word often becomes a symbol of intensity, unity, and fighting spirit.

But despite how familiar the term osu may sound, its origin and meaning are far from simple.

Most scholars and long-time practitioners trace osu back to the early 20th-century Japanese naval academies, not to the Okinawan roots of karate itself. The most widely accepted explanation is that osu is a contraction of two kanji 押忍:

- 押す (osu) — “to push” or “apply pressure”

- 忍ぶ (shinobu) — “to endure” or “persevere”

Together, they convey the idea of pushing through hardship with silent determination — a sentiment that aligned perfectly with the rigour of military discipline, and later, with the ethos of hard-contact karate systems.

Alternative theories also exist. Some suggest osu may have emerged as an abbreviated form of ohayō gozaimasu (“good morning”) or onegaishimasu (“please teach me”), especially in athletic or military settings where efficiency in communication was valued. Over time, the term filtered into various martial arts communities, eventually becoming ingrained in dojo culture across mainland Japan.

But while osu gained traction in some parts of Japan, it was never part of traditional Okinawan karate vocabulary. In fact, in Okinawan dojos, the word is often absent altogether — not out of stubbornness, but because it simply doesn’t belong to the island’s martial heritage. This cultural distinction is essential to understanding why the word is viewed with ambivalence, or even disapproval, in some traditional karate circles.

Osu, then, is a word with multiple faces: a rallying cry for some, a red flag for others. Its meaning is shaped not only by kanji and history, but also by culture, lineage, and intent.

Cultural Contrasts and Misuse of “Osu” in Budo

While osu has become widely accepted in some martial arts circles, its use is far from universal — and in some cases, even considered inappropriate. To understand why, we need to examine not just what osu means, but where and how it is used.

In mainland Japanese martial arts, particularly those influenced by military structure or full-contact competition, osu often embodies ideals like grit, discipline, and camaraderie. In these contexts, it’s used routinely and without controversy — a kind of shorthand for respect and resolve. You’ll hear it in Kyokushin dojos, in Yoshinkan Aikido, and even in some judo and kendo settings.

However, in Okinawan karate, the birthplace of the art, osu is notably absent. Okinawan karate culture places a high value on humility, politeness, and quiet respect — qualities reflected not only in movement but also in language. Okinawan instructors often favor words like hai (yes) or onegai shimasu (please train with me), which carry a more formal and nuanced tone. The omission of osu in these traditions isn’t an oversight — it reflects a deeper cultural difference in how martial etiquette is understood and expressed.

The divide becomes even more pronounced in traditional Japanese social settings, where osu can come across as crude or overly masculine. The word has long been associated with youth subcultures, sports clubs, and even yakuza slang — rough, direct, and lacking in refinement. In some cases, saying osu to an elder, a woman, or someone of higher status can be seen as impolite or disrespectful. Japanese teachers like Suzuki Tatsuo, Shiomitsu Masafumi, and Harada Mitsusuke have all voiced concern over its use, describing it as “rude” or “gangster talk.”

Yet in Western dojos, osu is often used with sincere enthusiasm but little cultural context. Many practitioners adopt it as a sign of respect or spirit, unaware of the discomfort it may cause in traditional settings. Others use it reflexively, copying what they’ve seen online or in films, not knowing its history or implications. In some cases, it has become a kind of social media signature — #osu — posted without thought or meaning.

This disconnection between intent and perception is where the misuse of osu begins. When a word is adopted without understanding, it risks becoming a hollow expression — or worse, a form of unintentional cultural appropriation. Even when meant respectfully, using osu in the wrong setting can lead to confusion, miscommunication, or unintended offence.

That doesn’t mean those who use osu are wrong — but it does mean we owe it to ourselves, and to our art, to understand where the word fits, and where it doesn’t.

Aligning Language With Lineage: What “Osu” Meant to Me — Then and Now

Like many karate practitioners outside Japan, I began my training with little knowledge of osu’s deeper cultural roots. In 1981, I started learning Hayashi-Ha Shito-Ryu, a lineage with traditional Okinawan roots. But the chief instructor at the time had a Kyokushin background, and as a result, osu was used constantly in the dojo.

We said it when bowing in and out, when receiving corrections, when acknowledging a partner, or simply as a way to show spirit and focus. It was used so often that it became second nature — a kind of verbal punctuation mark for all aspects of training.

At the time, I never thought twice about it. Like many beginners, I assumed it was part of karate’s formal vocabulary. Hai, sensei, arigatou gozaimasu, and osu — they all seemed to belong together. To me, osu was a powerful sound, full of energy. It felt like the right thing to say.

And for over two decades, I said it.

But that changed in 2003.

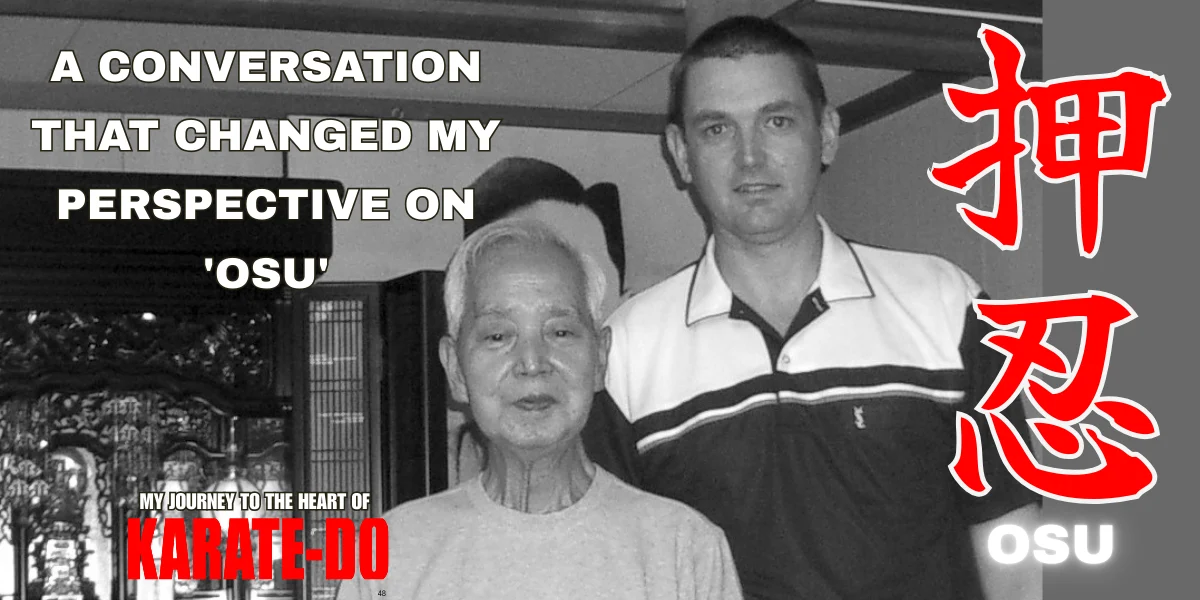

During a trip to Japan, I had the rare opportunity to meet Mabuni Kenzo Soke, the son of Mabuni Kenwa, the founder of Shito-Ryu Karate. The meeting took place in his home in Osaka — the same home, I later learned, that his father had lived in after moving from Okinawa. It was one of the most meaningful moments of my karate journey.

We spoke about many aspects of karate: philosophy, lineage, training. But one particular exchange has stayed with me ever since.

I asked him, “Soke, what are your thoughts on the word osu?”

He paused, looked at me with calm seriousness, and said:

“Osu is yakuza no kotoba — gangster language. I never use that term, and I don’t want it used by my students. In training, the proper acknowledgment is hai.”

He didn’t say it with anger, or judgment — just quiet clarity. He wasn’t dismissing other systems, nor was he telling me how to run my dojo. He was simply stating, without compromise, what osu meant to him — and by extension, what it didn’t mean within the art passed down to him by his father.

That moment left a deep impression on me. I had used osu for over 20 years, but I stopped that day — not because I suddenly believed it was wrong, but because I realised it didn’t belong in the lineage I was entrusted to carry forward.

It was no longer just a word — it was a reflection of values. And in Shito-Ryu, those values were better expressed through words like hai, spoken with quiet respect and clear intent.

Choosing Hai Instead in the Dojo

After that meeting with Mabuni Kenzo Soke, I returned home with a renewed sense of purpose — and a new awareness of the language I used in the dojo. From that point forward, I made a deliberate choice to use hai instead of osu, and to encourage my students to do the same.

This wasn’t a decision made lightly or out of obligation. It wasn’t about rejecting other systems, or telling others how they should train. It was about alignment — with the values of Shito-Ryu, with the example set by Mabuni Kenzo, and with the spirit of humility that lies at the heart of traditional karate.

Hai (はい) is a simple word. It means “yes,” but in the dojo, it means much more. It shows that you’ve heard, that you’ve understood, and that you’re ready to act. It carries no bravado, no unnecessary edge. It’s polite, direct, and appropriate in virtually every Japanese setting — from a classroom to a formal meeting, and especially within the traditional dojo.

When students ask me why we don’t say osu, I don’t just tell them “because we don’t.” I tell them the story of that conversation with Mabuni Kenzo Soke. I explain that words have weight — and that not all words carry the same meaning in every context.

Using hai is also a teaching moment. It reminds students that karate isn’t just about technique — it’s about intention. The way we move, the way we bow, and yes, the way we speak — all of it reflects the mindset we bring to our training. When we understand that, we become not just better martial artists, but more respectful practitioners of the art itself.

Some students are surprised to hear that osu isn’t universal. Others are relieved to learn that they can train hard and show spirit without shouting a word they don’t fully understand. In both cases, they walk away with something valuable: context, clarity, and a deeper appreciation for the role that culture and lineage play in shaping our practice.

We say hai not because it’s better than osu, but because it’s right for the karate we practise. And that distinction matters.

Broader Implications in the Karate Dojo

The decision to use or avoid the term osu isn’t just about personal preference — it raises broader questions about how we engage with karate as a living tradition. At its core, it’s about understanding the difference between adopting a practice and truly respecting its origins.

In today’s global martial arts community, it’s easy for terms, rituals, and customs to become unmoored from their cultural context. We see something online, hear it in a seminar, or pick it up from a visiting instructor, and it becomes part of our training without much thought. But tradition without understanding can lead to misrepresentation — even with the best of intentions.

This is particularly true with osu. For some, it’s a badge of dojo spirit. For others, especially those trained in Okinawan or classical Japanese settings, it can feel out of place or even disrespectful. When we use a word like osu casually or universally, without awareness of its roots, we risk flattening a rich and diverse culture into a single, simplified expression.

That doesn’t mean we need to overthink every word we say in the dojo. But it does mean we have a responsibility — especially as instructors and long-time practitioners — to model thoughtfulness in how we pass karate on to others.

So what does that look like in practice?

It means asking questions, even about the small things. It means recognising that what’s normal in one dojo might be inappropriate in another. It means understanding that respect isn’t always loud or forceful — sometimes, it’s quiet, deliberate, and culturally informed.

Most importantly, it means remembering that we are all — always — students of this art. Whether we’re white belts or black belts, the moment we stop being curious is the moment we stop growing. And if karate teaches us anything, it’s that growth and humility go hand in hand.

Conclusion

The word osu is small, but the conversation around it is anything but. It means different things to different people — perseverance, respect, unity, spirit — and in the right context, it can carry deep significance. But context is everything.

To some, osu is a vital part of their dojo culture. To others, especially in Okinawan or traditional Japanese settings, it is seen as brash, crude, or even inappropriate. As I learned through my own journey — and especially through my meeting with Mabuni Kenzo Soke — osu is not a neutral term. It comes with history. It comes with implications. And it carries weight.

That’s why I no longer use it in my own dojo. Not because I think others are wrong to use it, but because I believe in aligning my words with my lineage. I say hai — and I teach my students to do the same — as a way to honour the traditions passed down to me, and to train with intention, clarity, and respect.

At the end of the day, karate gives us room to ask these questions. It allows us to explore, to reflect, and to refine the way we move, think, and speak. And that, I believe, is one of its greatest strengths.

So whether you say osu, hai, or choose silence — say it with understanding.

And never stop learning.